Building a Better Batmobile: The Morrison Batman (Part 1)

Part 1: The Morrison

(and Miller) Batman Before Morrison’s Batman Run Begins

Oh man, it’s been 4 years since my very first post here,

and it’s my 100th post SIMULTANEOUSLY. To celebrate, let’s talk about Batman.

(nu-na-nu-na-nu-na-nu-na-nu-na-nu-na-nu-na-nu-na-nu-na-nu-na-nu-na-nu-na-Bat-man!)

And by “talk about Batman” I actually mean “start a

series of articles on Batman”. Because I

have a lot to say about Batman, you guys.

Spoilers for

comics! (Some of them more than 20 years old, others that just came out a

few months ago…)

Warner Brothers recently released Part 2 of their animated

adaption of the Frank Miller-Klaus Janson classic The Dark Knight Returns. If

you aren’t familiar at least in some way with the comic, I have no idea what

you’re doing here, but welcome! Short

version, TDKReturns sort of redefined

Batman in a some ways (but probably not as many as it gets credit for). TDKR and

Miller’s follow up Bat-story, Batman: Year

One (with David Mazzucchelli on the art side) were largely responsible for

a resurgence in Bat-Mania, and both had a huge impact on the Batman films from

Tim Burton and later from Christopher Nolan (multiple scenes from Batman Begins were lifted wholesale from

Year One). Basically, the “Miller Model” of Batman

became the standard version of the character in the mid-80’s, replacing the late

60’s “O’Neil Model”.

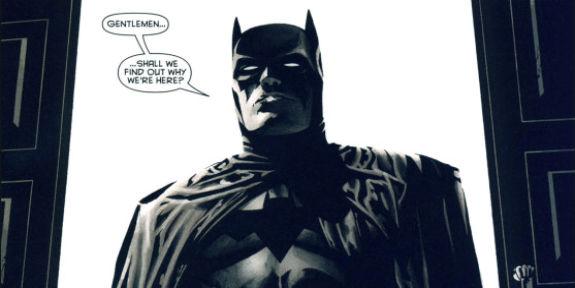

(The “Miller Model” of Batman, submitted rather unfairly without

context)

Now this is not a review of the cinematic version TDKRrturns, because I find it difficult

to really review it. They made some

interesting style choices, but ultimately they stuck as close to the source

comic as possible, almost to the point of fanaticism. They didn’t want to make a Batman movie based

on a comic; they wanted to turn a comic into a movie verbatim. The one major aspect of the comic that they

dropped was something that could never come off as anything other than cheesy

in a movie: In the comic, nearly every single major character is given to

literary narration of the events unfolding around them. You really dive into the characters heads,

understanding their motivations and personalities, because their thoughts inform

your views of them. In the comic, it’s

genius. My favorite bit is from one of

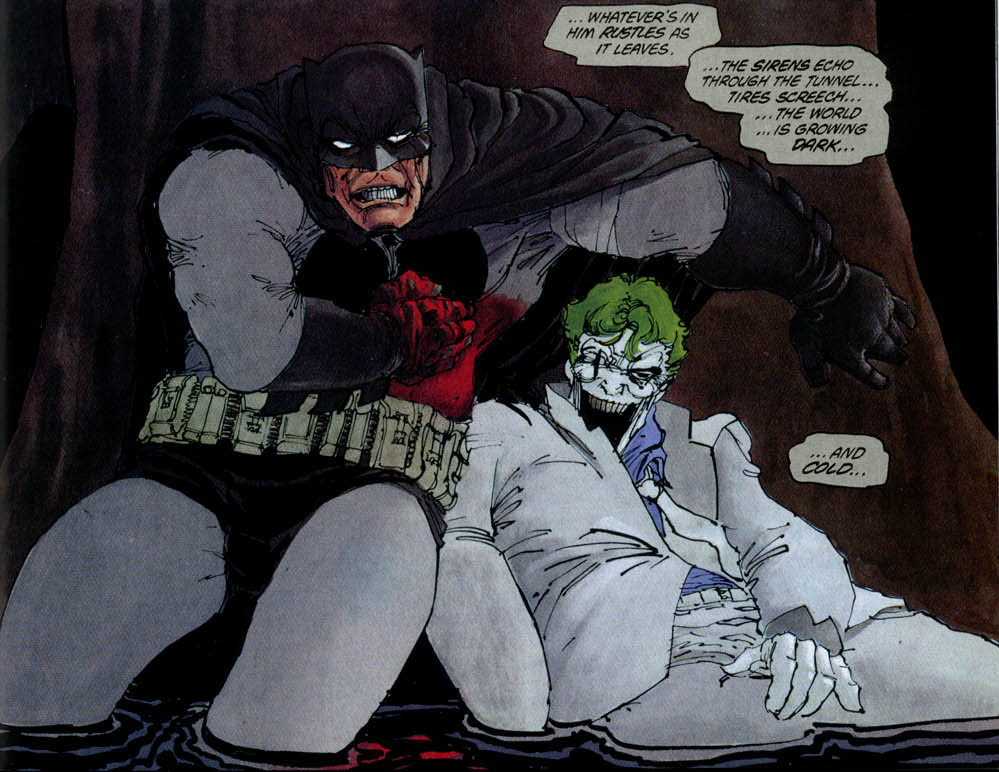

these “narrative thought boxes”, after the Joker has murdered a few hundred

talk show audience guests. “No, I don’t keep count {of the bodies]” Joker

thinks. “But you do…”

("…And I love

you for it.")

And then he murders a bunch of cub scouts with poisoned

cotton candy. Super creepy, and super

awesome.

A comic is all visual, though, and movies are both visual

and audible. In a film, the only way to

know exactly what a character is thinking is for them to either say it out loud

on screen, or to have them narrate the film as it goes along. And multiple voice overs throughout the

entire movie would get pretty boring and possibly confusing very quickly- so

the filmmakers (fairly wisely) just cut them out. It was probably the smartest way to go, but

it also completely changes the dynamic of the story. Now, instead of reading the thoughts and

feelings of the characters, all I can see is their actions. Removing the internal monologue of TDKReturns turns it into a fairly linear story

that becomes VERY violent and weirdly political about the Reagan years, and

then Batman just punches the living shit out

of Superman. That caught me off guard

watching the film*, but perhaps it shouldn’t have.

I’m not saying that’s bad. Actually, it’s quite revealing, and

telling. It’s telling because of what

came after Miller’s run; the popularity of his interpretation meant that many

writers tried to imitate his style. Most

of them have done it quite poorly. As a

general rule, they’ve missed the heart of the story, just like this film does,

by not fully understanding the context, and thus they have rendered a Batman

that is a morally questionable, bizarrely asexual, repressed, violent, crazy

person. And make no mistake, a lot of

people like Batman like that, and of course, he is a character open to multiple

interpretations. There are plenty of

Batman stories that take the character as deadly serious. I just think they’re acting like 12 year

olds, and so does (I think) Grant Morrison.

Morrison has, in one way or another, been writing Batman

for 25 years. Starting with Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious

Earth, through Gothic: A Romance,

his JLA run, and the Batman stories

(over multiple titles) he’s been writing since 2006, Morrison has been working

to redefine the character. The “Morrison

Model” has been called several things before: “Zen master”; “ultimate planner”;

in his comics Morrison has had characters state that Batman is “the most

dangerous man on the planet” and that “Batman thinks of everything”. I have my own suggestion. The “Morrison Model” of Batman is that Batman

is constantly trying to make himself a more perfect man. And almost every Batman story he’s been

telling has been directly about that.

(This is the cover.

It’s the first indication that this is not a typical Batman story)

Rebuilding Batman and making him better was Morrison’s

original goal in Arkham Asylum. It’s April Fool’s Day, the Joker and crew

have taken over the Asylum, and they’ll only surrender if Batman will descend

into the darkest pits of the madhouse and confront it’s- and his- psychological

demons. By taking all the parts of the

then-recently developed “Miller Model” of Batman, and forcing the character to

be confronted by all of his intimate fears, by his entire psychosis, Morrison’s

goal was to “fix” the character, so that we could have Batman books that weren’t

so obsessed with how irrational Batman’s actions were. Along the way we got a really trippy journey

through the madhouse, the expanded history of the mad house’s founder, and lots

of talk about magic and tarot and stuff.

In the end, Harvey Dent gets to be the subtle savior of Batman, earning

his own moment of redemption. It’s also

a little too on the nose about all the maternal feelings and stuff, but maybe I’ve

just read it a few too many times.

(The Joker, in Arkham

Asylum. This is definitely not a

typical Batman story.)

Maybe it’s because it was a little too dark and brooding,

maybe because it wasn’t done in the “DC house style”, or maybe just because

fanboys don’t know what’s good for them, but Morrison’s attempt to fix things

didn’t really take. His follow up, Gothic is fine, but by no means

essential. Following a lot of the same

theme’s as Arkham, Gothic takes place in Batman’s early

years, and deals with a mystic enemy. Mister

Whisper is an evil monk, promised 300 years of life in exchange for his soul

has almost run out of time on that barter.

The Sacred Architecture stuff that was mostly just implied in Arkham is brought to the forefront

here. And instead of focusing on Bruce’s

mother, it’s his father that gets the spot light. Rather than a Deus ex machine, it’s the Devil

in the Machine that wraps up this story- which is mostly interesting because

Morrison would return to that theme 15 years later. There’s lot’s of Gotham as hell, evil

cathedrals, and Don Giovanni is thrown into the mix. Whisper is pursued by two devils, Batman (see

the ears) and a young girl who is more than she appears. There’s more to it than that, but again, not

all that important for “Morrison’s Long Run”.

(Batman: He is King of Hell.)

What is essential is Morrison’s JLA run. It’s awesome, and

if you haven’t read it, you absolutely should.

I’m not going to go into too much detail on it, because there’s a lot to

it and there are a whole bunch of story arcs.

What matters here, though, are Batman’s interactions with the team. Morrison’s JLA pretty much lives and breathes on the idea that Batman always

has everything figured out. He’s always

6 steps ahead of everybody, good guys and bad guys included.

(Batman: He knows your secret.)

Since all the writers in the regular Bat-books were

basically still ape-ing Miller’s take, Morrison decided to trail-blaze his take

interpretation of the character in JLA. And in many ways, Batman gets the best

character arc of any of the “big seven”.

It’s not a huge emotional roller coaster or anything, but trust me, when

Bats takes down Prometheus, the moment feels earned.

(Trust me, this feels earned.)

But if you had to sum up Morrison’s take on Batman (so

far) in one page, it would be this one:

(Spoiler: Batman’s Flying Saucer had, in fact,

arrived. From his Flying Saucer

Factory. That he owns.)

“Don’t tell my friends in the G.C.P.D. about this.” As if to say “Fine, fine, you ‘serious’ kids

can have your dark, brooding Batman in his (many) solo books. What with your evil clowns and clay

monsters. That are serious. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I have a city of possessed

superheroes to save from an evil telepathic gorilla.” Morrison’s Batman embraces how truly weird

superhero stories are, and it revels in it.

The concept of Batman is “Dude in a Dracula costume punches bad dudes

dressed in question mark costumes.” It’s

totally ridiculous! Which is fine,

because it’s totally awesome too! Why

does everybody take this so seriously?

And so, after a decade of, off and on, writing a Batman

that was king of the awesomes, Morrison was handed the solo Batman book. And what was the first thing he did with

it? He saddled Batman with a kid he

never knew he had. Trust me, this will

all make sense eventually.

Next time: Batman and Son! Plus some other stuff too!

*=Not the shit-punching out of Superman, the graphic violence. To be clear.

Comments

Post a Comment